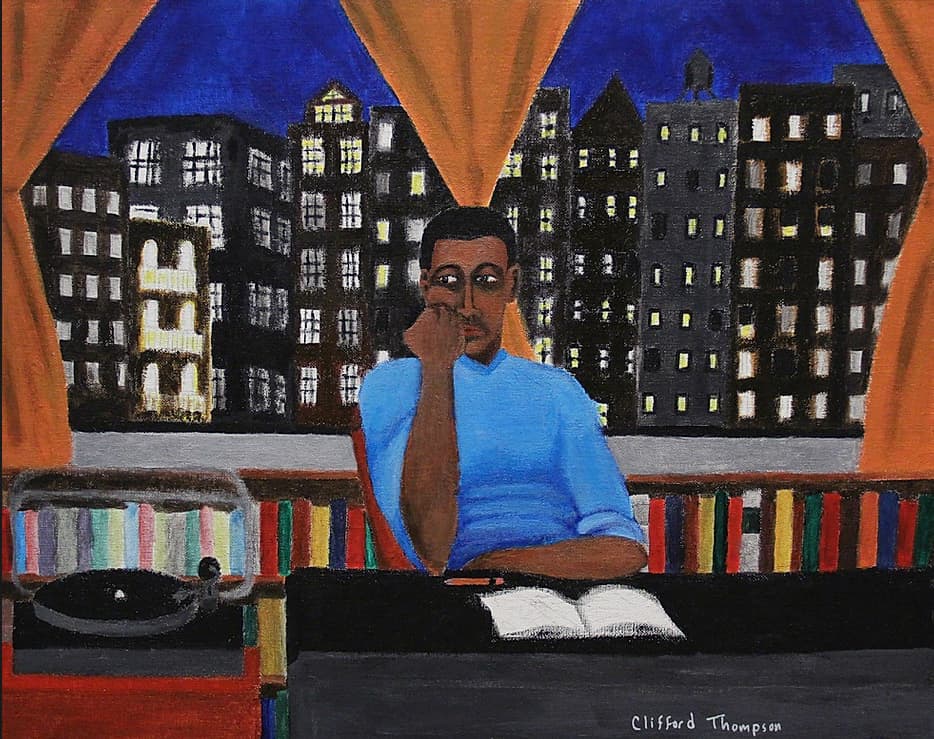

Clifford Thompson

Malcolm X has been on my mind lately. I’ll get to that in a moment.

In my early and mid-teens, I played the clarinet, badly. I gave it up after that, and I don’t even know where my old clarinet is. But I have another one now, given to me by a friend who found it in her apartment, left behind by a previous tenant; my friend thought of me as she herself was preparing to move out. The clarinet has mostly stayed in my closet, forgotten—until recently. Most evenings at seven, when the clapping and cheers begin for health care workers pushing on bravely in the face of Covid-19, I open my window and add to the din, trilling two notes, an open G and F sharp, until the clapping and shouting and banging wane, or until I get tired. It is in these moments, holding this sleek black instrument, that I think of Malcolm X, who is shown in a famous photograph standing at a window in his home, dressed in a suit and tie and holding a sleek black rifle. Each evening I chuckle at the absurdity of the comparison. Then I stop chuckling, and a sadness overtakes me.

Malcolm was thirty-nine when he was killed, in 1965. I am nearly two decades older than that now, but Malcolm will always feel like an elder. On the whole I have always been a bigger follower of Martin Luther King Jr. than of Malcolm X; I am a peaceful person by nature, and my wish, as laughably unfashionable as it is, is for people to get along when possible. But if King were my father, Malcolm would be the uncle whose visits I secretly couldn’t wait for, the one who said so many things I absolutely disagreed with and so many others I would dismiss, I know deep down, at my peril. King’s message and actions brought out the best in many of us, and it wasn’t his fault if they also brought out the worst in many others. But there was something in Malcolm’s message—something that kindled an often shaky pride and self-respect, something that spoke to a righteous anger—that touches a chord in most black people too, whether they’ll say so or not, and many will, quite proudly. (It should be said that King was a more radical figure than many today take him for, and it is not acknowledged often, or often enough, that at the ends of their respective journeys, the two men were not all that far apart ideologically.)

I feel sad because I know Malcolm would feel sad if he could see us now—if he could see this peculiar moment in our journey, if he could see his warnings seemingly borne out. Malcolm dreamed of a separate nation for black people, scoffing at the idea that we could ever get a fair shake in this one, and the more time that passes, the harder it is to dismiss his view out of hand. Covid-19 is only the latest development that is bad for the country as a whole but worse for African-Americans. Of the nearly one hundred thousand Americans who have died from the virus, the number of blacks is disproportionate to the percentage of blacks in the nation. That is partly because many black people have preexisting health conditions and jobs that expose them to the public; that, in turn, is because people of color are often lower down on the economic totem pole, and the many reasons for that share a root cause, which is racism.

For many years now, more than seem possible to me, my wife and I have shared a two-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn. This is where we raised our children, who are now grown and living elsewhere. And this is where, for two and a half months and counting, we have spent nearly all of our waking hours and seen only each other. Until I was eighteen, I lived in the same house, but when I think of that house, what I picture is the view from my bedroom window of the one across the street; similarly, when I think of my current home, it is not my own face I see but my wife’s, and she would probably say the same about me. I am black. My wife is white. We are sort of a microcosm of the country, or of what the country would be if its demographics were slightly different and its different groups cared more about one another.

We go quietly about our days. Much of my work pre-Covid was already done at home, so our current life has not been a huge adjustment for me that way. My wife’s work has been more affected by her having to be here. She manages. We manage. I get up early and read and listen to music until she wakes up. We greet each other with tight hugs and then have coffee in bed. Then we mostly go to separate parts of the apartment, seeing each other occasionally, checking in over dinner about our respective days. Sometimes we watch movies together in the evenings. Comedies are great during this time. I can recommend, if you haven’t seen it, Frank Oz’s Bowfinger, with Steve Martin and Eddie Murphy—I hadn’t heard my wife laugh like that in weeks. Other nights, she watches documentaries while I paint in the same room, an arrangement we both like. It’s not ideal—I miss movies in a theater, book stores, bars, my local diners, the Y, art museums—but it’s comfortable.

One of the strangest things about our routine, in fact, is how comfortable it is, in contrast to what we know has been happening outside, which of course is death on a fairly massive scale. The closest contact I’ve had with it are the times when I put on mask and gloves and go to the grocery store, which, during the period when New Yorkers were dying of Covid by the hundreds daily, made me feel like a character on a mission in a World War II movie.

And this weird disconnect parallels what I felt a lot of the time pre-Covid. I live in a very nice, very comfortable neighborhood where there are not a lot of people who look like me, while a lot of people who look like me are in prison—largely because of the so-called war on drugs, a manmade virus that targets people of color. It is not quite accurate to say that I haven’t done anything about that or about other issues facing blacks—I’ve taken part in protests, I’ve made calls—but I’ve done it fitfully, while wondering if it does any good, if my puny and inconsistent efforts matter at all in the face of such enormity.

Like many people in this city where space is at such a premium, I sometimes have dreams—not fantasies: literal nighttime dreams—of finding another room in my apartment I didn’t know was there. My wife brilliantly came up with something approaching a real-life answer to this. She placed a little table of ours beside a window in our bedroom; it would not have occurred to me that this little table could hold dinner plates for two, but it does (small ones), and sometimes now we dine there, with a view of brownstones and people and leafy trees, now that spring is here.

I like to think I might also find, not in my apartment but in myself, not rooms, but room—room for more contributions, room for thinking about other ways to make my voice heard. I have written about the issues close to my heart, which can feel like blowing notes into the wind. But perhaps that is the wrong way to think of it. Perhaps is it important to understand that the real enemy is despair, that it is better to find what one can do, with the knowledge that it may not make much difference, than to do nothing.

In the meantime, at seven most evenings, I blow my black horn, adding to the noise. I blow it for those brave health care workers. I blow for black and brown people in prison, too. And a few of those trills go out, though no one hearing them knows it, for Malcolm.