by Steven Cheslik-DeMeyer

I think you’re going to like my new work, by the way. I’m anxious to show it to you. (Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, undated, 1987.)

I never forget Joan’s birthday because it is the same as my mother’s, September 1. I never forget the date on which Hitler invaded Poland and started World War II because it is the day my mother was born, September 1, 1939.

Joan’s Apartment

Can you do me a huge favor? I am looking for a short story which I believe is by Jorge Borges—called (I believe) “The Wall and the Books.” It should be in my books in my apartment, if you care to go there and look [. . .] I haven’t had any luck finding it here, so maybe my memory failed me somewhere with the title or the author—but even if I’m wrong about the author’s name—which I don’t think I am, there aren’t so many collections of short stories in my bookcase (by one author) and so it can’t be so hard to find. As I recall, it’s only 3 or 4 pages long—and it’s about the Great Wall of China—something else just occurred to me—Kafka wrote a short story to that theme, maybe you could send that also (and if you don’t find the other one maybe the Kafka one is what I’m really thinking of, but I don’t think so.) (Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, undated, 1987.)

For a while, there were three of us in the small two-bedroom apartment on East 10th Street between 1st Avenue and Avenue A. In the smaller bedroom, Joan had built over the door a sleeping loft big enough for two twin mattresses. This upper loft was the width and nearly the length of the room, leaving just a couple feet at the end by the window (there was a ladder there which we climbed to go to bed) and halfway down the wall, another loft half the size of the upper one. There was no space left for anything else in the room. Joan’s scheme was that we would all sleep in the small bedroom leaving the (only slightly) larger bedroom for a shared studio.

P.S. Tomorrow it will probably seem entirely different. (Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, June 29, 1987.)

I don’t remember any of us making art in the bedroom studio. I do have a clear memory of Joan naked, sitting on the floor in the living room/kitchen while I and a small group of friends drew her. I had seen artist’s models nude before but never a woman I knew. In my memory she’s sitting on newspaper.

Now I am sitting outside [my studio] (though it’s dark and cold) (the page is illuminated by a neon light over the door) and writing this—waiting for someone who I’m not even sure will come—and getting ready to leave because I want to go home, and I don’t think she’s coming.(Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, undated, 1987.)

On second thought, now I remember that our third roommate, S., for a time used the studio to paint wooden duck decoys, all of them along the wall assembly line style in different stages of finish. She painted and sold them I assume to make a little pocket money. S. didn’t live with us in the apartment for long; I don’t remember why. The lower sleeping loft was probably used mostly for storage. Later, when it was just Joan and I, I took the smaller bedroom and Joan took the larger one.

Things with X. go well—but of course not unblemished [. . .] His idea of being realistic is stressing or maintaining the fact that we will not be together “forever.” He is very sure of that because he is sure (as a matter of intellect) that relationships today do not endure—because he knows, because it’s a fact [. . .] “it’s a normal part of development for one to have lots of different relationships and neither one of us has had so many, so much experience in that respect, hence [. . .]” and then I start feeling angry/frustrated/tense—like, what did I come here for if the discussion centers around (not always, but once is more than enough) when the relationship is going to dissolve? (Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, May 6, 1987.)

We had an old-fashioned red rotary phone that rang loud. The cord was very long so Joan could talk and do other things at the same time, that cord stretched across the apartment, a red line dividing it in two parts constantly shifting. Pablo only comes to mind because of that red phone.

I may be giving up my apartment. . . . The idea of doing that is a little sad/a little frightening, but I can’t keep feeling myself tied to NY—or that apt. At least, because of fucked up real estate attitudes. If I do have to do this can I ask you for a few favors a) help! b) maybe I’ll stay with you guys (in July)? c) if I do move back to NY someday maybe I can stay with you guys till I find a place, or in the interim, or something? I’m not sure if I will ever move back to NY—I really want to live in NY some day—but not like an animal of necessity. Oh, I am a confused child! (Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, May 6, 1987.)

A boy, Pablo, who cruised me in the stairwell of the main Parsons building and we exchanged numbers—after a year at Parsons I dropped out and, among other jobs, worked briefly as an assistant to Kestutis Zapkus, a painter who taught there, and I stayed in New York for a year before moving back to Indiana where I’d planned to finish an undergraduate degree but a few months before I left New York I met Eduardo and fell in love, so I only stayed in Indiana for a semester before moving back to be with him—but before all that, Pablo called the evening of the day we met and when Joan asked if she could tell me who was calling and he said, “Pablo,” she laughed loudly and repeated, “Pablo!” handing me the receiver. I was embarrassed and furious. I went to meet Pablo where he lived with a much older man in a studio apartment in the West Village. The older man had friends over and they all talked and laughed and ate dinner while Pablo and I took our clothes off and got into his bed, which was only two or three feet from where his roommate and his friends were socializing. I think we had sex under the covers but I can’t be sure all these years later. The things that didn’t seem strange to us when we were young.

The gut feeling of uprootedness . . . is almost incommunicable, especially as it is an emotional reaction to invisible, unmeasurable, circumstances. I feel “ok,” but when I consider months/years of continuing to live with this feeling of “not belonging,” “not fitting in,” I paralyze. (Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, undated, 1987.)

I met Eduardo, my first serious boyfriend when I was 22, after I had dropped out of Parsons and spent a year working and trying to be a painter but it wasn’t sticking. We’d met, or rather stared at each other, when I was assisting Kes Zapkus with a class that Eduardo was taking, but then I saw him at The Bar one night and the friends I was with (Joan, I think, among them) goaded me into approaching him. I had had a couple of beers and smoked some pot, so when I stood up my blood pressure fell, and I nearly fainted into his arms. We were inseparable until I moved back to Indiana in the fall to try to finish school, a plan which was already in motion and unstoppable before Eduardo was in the picture. We wrote to each other and talked on the phone every day for four months. I kept his letters in a shoebox which the following April I would throw into a dumpster on Avenue C. While I was in Indiana, Eduardo sent me a Polaroid of himself with a small lock of hair taped to it. He had dyed his hair green and wanted me to see it. In December, I abandoned my school plans and returned to New York and moved in with him where he lived on 11th Street near Avenue C. Things fell apart quickly, but I stayed four more months until one night, soon after I had moved into the second bedroom, he brought home a boy he’d picked up at a club, and I kicked a hole in his bedroom door. Eduardo later married a woman, an artist, and they had a child together, but I only know this through mutual friends. We were never in touch again. In August of 2002, I was in Edinburgh performing in the festival, near the end of my relationship with J., and I suddenly became curious about Eduardo. I emailed Joan who contacted a mutual friend who had been close to Eduardo in school who told her, and then Joan told me, that Eduardo had died of AIDS in 1992.

The weather here is not so great. Too chilly. (Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, May 6, 1987.)

After leaving Eduardo, I lived on Pitt Street near the Williamsburg Bridge in a very small railroad flat. It was the first time I’d seen one of those door locks that consist of a metal pole braced against the door with the other end anchored in a divot on the floor. One night on my way home late in the rain I saw, or maybe heard first, a kitten on the stairs leading up to the entrance of the church on Pitt between Rivington and Stanton. He was quite small and it was raining, so I took him home. He had something black, tar I think, spattered all over his face which took me several days to remove, bit by bit. I named him Honey and he lived with me until he died 15 years later.

I have so many things to “tell you”—if you were here, how many hours would we sit and talk, how many Kleenex would I moisten, how many times mightn’t I ask you for a hug [. . .] I moved my things out [of X.’s apartment] the other day, into U.’s apartment. As I packed I listened to the cassette of songs I had recorded for X. [. . .] I feel as though I can’t come back to New York, or rather, leave Berlin, until I get something accomplished here. [. . .] I’m so sad, and feel very small. (Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, August 24, 1987.)

That New York Times article (“Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals”), usually taken to be a declaration of the beginning of the epidemic in the United States, appeared on July 3, 1981. I moved to New York from Ohio in late August.

It finally got hot yesterday and today—it’s not even as bad as NY, but felt awfully (unbearably!) hot because it was so unexpected. I am sitting on the balcony writing this. Did I ever tell you that we live on a canal? In the summer the boats ride by. . . it’s fun to see them. (Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, undated, 1987.)

Though there were certainly people with HIV all around me, I had no idea of it, for months, years in a way. My art school friends didn’t talk about it, and, even as we became aware that it was near us, that it was deadly, that people were disappearing, I can’t say that I took it seriously, or not any more seriously than any of the other dangers our world was made of, not, at least, until much later when ACT UP gave me something concrete that I could do about it. I didn’t get tested until after I left B. in 1989. Poverty, addiction, crime, risk, disease, outsider status, stigma—they were the water we swam in, maybe even what we came for.

I worry about my friends, about Matthew, about you, B. . . . And I don’t know whether knowing is good or bad, or wanting to know or what. Since I have known about Matthew I think a lot about AIDS . . . a lot about mortality. For a while it was really very difficult. As for finding out that one doesn’t have the virus, of course that would be a relief. What would you do if you found out you had it? Would you change your lifestyle? quit smoking? exercise? eat well and regularly? These are things which you can do apart from waiting/being a guinea pig. Matthew is a guinea pig—in some ways all AIDS patients are—in his case he happens to be, until now, and hopefully for a long time coming, one of the guinea pigs who responds well to treatments.(Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, September 9, 1987.)

Lady Bunny, the Pyramid Club, Ethyl Eichelberger, 3 Teens Kill 4, The Bar on Second Avenue, heroin, Rolling Rock, the pot dealers on the corner of First Avenue and 10th who accosted us like tourists on our way to and from home every day all day long, and the homeless in tents in Tompkins Square Park, the hippie grocery store on First Avenue, and Angelica, the herb shop next door with long shelves of great glass jars full of dried echinacea and goldenseal, the Second Avenue stop on the F, the First Avenue stop on the L, the post office on 14th Street where you never waited in line for less than half an hour and at least 50% of the time they’d lost or beaten the shit out of your package. Leshko’s for chicken livers, Odessa for meatloaf and gravy, Kiev for $2.50 pea soup that came with two thick slices of challah bread, the bakery next door for hamantaschen.

I feel a bit numbed at the moment, because I haven’t the slightest idea how to really deal with these feelings . . . and so I try and cancel them out a bit. (Earlier I didn’t . . . and it was quite difficult.) (Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, September 9, 1987.)

Joan used to use an expression, “what my mother would think is real,” to mean the quotidian, the bourgie, the obvious, the tedious realm where everyone else lived. We rejected it all. The East Village was fuck off to the world and at the same time an understanding that we were the only world worth caring about, the avant-est of the avant garde of fashion, music, art, ideas. On some blocks half the buildings were bombed out, burned up, falling down, and we walked around as though we’d blown them up ourselves.

I hope you can come visit—I’m missing you, and it does help to know that thousands of miles away you’re still loving me and thinking about me. Thanks for the reminder! I’m going to wrap this up. I hope it’s not too much of a problem that I’m so incomplete about some things . . . I’m starting to feel gaps in my ability to communicate clearly in English! (Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, September 9, 1987.)

Soon after Joan and I met in Regina Granne’s painting class—Regina who smoked as many cigarettes as we did, who taught us how to clean our brushes with a piece of wire window screen, who said “When you’re looking at a painting, you’re looking at paint” and “Your parents will never understand”—just days into the semester, I was complaining about my roommates in the Union Square dorm who stayed up all night listening to prog rock, and Joan invited me to move into the apartment she was renting on East 10th Street just east of First Avenue. We made plans for me to come over and see it, and she told me (had I asked?) that the block was safe but not to get freaked out on my way there because the block between First and Second Avenue on 10th was dicey.

Then a visit to Tim in Milan. [. . .] The situation is such: Pietro is in the hospital with what was first diagnosed as t.b. (tuberculosis, right?) and what they say now is pneumonia. Anyway, the hospital is away from Milan (a short train ride) close to where Pietro’s mother lives. Tim is depressed (though dealing well) not only because Pietro is sick, but also he may be in the hospital for a while, Pietro’s mother is being what Tim calls typically Italian mother and pampering/protecting/shielding him—wants him to come to her house rather than back to Milan when he is released from the hospital, which he (Pietro) is in agreement with (what Tim describes as typical Italian son) and what Tim is not at all happy about (it would mean Pietro comes back at the earliest in the spring, all of which is naturally difficult for Tim.)(Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, September 9, 1987.)

My mother and father visited me in 1982, their first trip to New York. They parked their car somewhere near the Gramercy Hotel where they were staying (my father still tells the story of the woman in the car behind him who unleashed a barrage of obscenities at him when he stopped his car in front of the hotel to unload their bags) and walked down to 10th Street. I was at work when my parents arrived. (My memory tells me that I was working at Pearl Paint on Canal Street, my first New York job, but how important is it really to make the timeline accurate now?) When I got home, they were sitting on straight-back chairs on the only exposed floor space in the living room. A friend of ours, F., was between apartments and Joan had offered to store his belongings and furniture, including a queen-size bed, mattress, and box springs upended and stacked against the wall, in our living room, which I’d guess was about 80 square feet. My father looked shell-shocked. My mother was on the verge of tears.

I can understand your fears, worries, anxieties about AIDS. I know it’s a different thing for me to be thinking about it (I worry myself about cancer, constantly struggling since I’ve left NY to give up smoking again, feel weak, know it’s bad for me, think I must already have some kind of cancer festering away in my innermost cavities) [. . .]. (Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, September 9, 1987.)

I should use the present tense because Joan still has that apartment. And over many years, Joan has stored the belongings of many friends in one kind of jam or another. When things went south with Eduardo soon after I abandoned my degree plans in Indiana and moved back to New York and into his apartment on 11th Street between B and C, after I untied the necktie that I’d tied around a pipe near the ceiling and got down from the chair I was standing on, walked into the living room and threw a glass against the wall and shattered it, I called Joan. She came over and helped me drag all my stuff, though no furniture, to 10th Street, and she kept it all for a few weeks while I stayed with my friend D. in Chelsea until I found an apartment for myself on Pitt Street and Delancey.

I hope you’re really serious about the prospect of coming to visit. I wanted to ask you if you could do me a favor—depending on when you come if my tools aren’t yet here if you could bring them. (Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, July 6, 1987.)

Joan and I both loved liverwurst. We bought bread from the tiny cavelike kosher bakery on 9th Street just west of First Avenue, two or three steps down from street level, the blackest black bread you’ve ever seen. An ancient man with long yellowish curls of a type I’d only seen in old German illustrations of Saint Nick would take the loaf you picked out and slice it using a terrifying machine with dozens of spinning blades. We took sandwiches made with this bread and thick slices of liverwurst with us to school for lunch. If we didn’t have time to make lunch or if we forgot I would have a Snickers bar and a Tab, and we all smoked lots and lots of cigarettes.

At some point, I have to begin really tackling the problem of where I am. (Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, undated, 1988.)

I didn’t know Matthew well. Joan and Matthew had done their foundation year at Parsons together, and then Matthew dropped out; I joined Joan’s class the following year, and Matthew was no longer in school by then, but he was around from time to time. I was jealous of him. Everyone, especially Joan, loved Matthew, and I wanted to be the one everyone loved. He was the handsome, well-read, bohemian artist I worried I was only pretending to be.

I just got your letter and am responding immediately [. . .] because I want to have very fresh in my mind/heart/soul—whatever—the feeling that someone “touched” me. It is so barren here sometimes in that respect. Your letter was like a conversation—like you explaining to me what’s going on—and I want to hold onto that feeling as long as possible. (Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, May 6, 1987.)

Joan and I argued constantly about housecleaning. I was not a fan. Of cleaning, or arguing. Once, when Joan was angry with me, I asked her if she wanted me to move out. She said, “Why is it always fight or flight with you?”

Matthew is well, but not. He has developed another skin condition, hasn’t yet gone to the doctor and is concerned. I am concerned as well, and my whole set of feelings toward Matthew hover in a kind of world of waiting. (Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, May 6, 1987.)

Winter of 1982–83 I caught a cold and it turned into a sinus infection which turned into a bronchial infection and pneumonia. I remember sitting on a ratty upholstered chair in my bedroom, the small one, removed of its many lofts, with one window onto an almost completely dark airshaft, feverish, unable to stop coughing, and Joan walking me to Beth Israel a few blocks north on First Avenue and waiting all night long in the E.R. waiting room, and a boy I was dating at the time was there too, P., a gentle but passionately political boy who hated when I used the expression “flaming faggot.” (Where had I met this sincere, principled character, who sat there for hours with us? P. is now an Episcopal minister.) A young gay man in a New York emergency room with pneumonia should have raised a red flag for doctors by 1983, but probably didn’t. I was sent home with a prescription for antibiotics. I quit smoking many years ago, but I still remember the raw feeling of inhaling cigarette smoke when I was sick, how if I was sick enough I wouldn’t smoke for a day or two at the most but usually I wouldn’t stop even if it hurt. When I returned to work at Pearl Paint after being out for a week with pneumonia, I was standing just outside the front door, underdressed for the cold wet day, finishing a cigarette at the end of my lunch hour, and a co-worker, an older woman, one of the cashiers, scolded me for smoking after I’d just been so seriously ill. The incident stands out now because I don’t remember having much contact with sensible adults during that time.

As for your doting tendencies with the cats—I’m the last person who you need to explain such a thing to, I understand these instincts quite well [. . .]. I have a lot of trouble thinking about such stuff too though, also because of being a woman and having a tendency towards castigating myself for “falling prey to such normalcies,” also when seen in a political light. (Woman/mother conflict! Artist?) Who has the time? [. . .] I think of how I want to “become successful,” the amount of craziness which goes into being an artist, showing, applying for this and that. It’s so difficult to imagine that with a kid. Maybe I won’t be satisfied with teaching or something, but at other times, I have an expectation to fulfill of being not just one of every 3rd artist living in NY. Do you understand? I know this sounds awfully immoral, considering how one is supposed to think of art as this sacred realm, but I’ve begun recognizing that my spirit needs other nourishment than aesthetic in order to keep on . . . of course a few months from now that may all change. (Letter from Joan in Berlin to Steven in New York, undated.)

Berlin

Remember the conversation we had shortly after your first decision to go back to Indiana? When you talked about the location and the form of your work? How maybe if you weren’t in New York your work would be very different etc. [. . .] And you felt uncertain or at least irked by the provinciality of that—the implication that it is somewhat like a change of clothes for a different climate. (Letter from Joan in Rhinebeck to Steven in New York, July 10, 1983.)

I wrote Joan recently that when Trump was elected, in an effort to get my bearings, I started re-reading Christopher Isherwood’s account of Berlin in the 1930s. It occurred to me that it must have been Matthew, or possibly Joan through Matthew, who recommended Isherwood to me in the early 1980s, which led me to read all the Isherwood. I’ve read most of his books now two or three times, the Berlin books even more.

I am on my way now. Feeling isolated a bit. So many people can and already have consolidated the two activities into one—the art, the politics—the activities of their thought and spirit combined in an impassioned way. But then most of them are creating transitory marks, temporal themes which carry weight no longer after the chapter is closed. Even given a specificity of situation, I believe that one must be able to extend to the general, to the pervasive, to the other pieces—that which float around in other places under similar guises. (Letter from Joan in New York to Steven in Indiana, November 22, 1983.)

“Hate exploded suddenly, without warning, out of nowhere [. . .],” Isherwood writes in Mr. Norris Changes Trains, about the Nazis. Suddenly, or so it seemed to us in our twenties, with the election of Reagan and the rising influence of Jerry Falwell and the Moral Majority, the whole world was interested in (interested, that is, in judging) what we did in our bedrooms, bars, baths, parks, beaches. I look back and marvel at how we all just went on, in the face of such danger and calamity, making art with each other, making dinner for each other. We were outraged, but we’d been outraged as long as we’d been conscious. It wasn’t exactly new.

MISS YOU—TAKE FUCKING CARE OF YOUR COLD YOU BASTARD. I DON’T WANT TO FIND YOU MOVED BACK TO INDIANA WHEN I GET HOME. (Letter from Joan in Amsterdam to Steven in New York, September 28, 1984.)

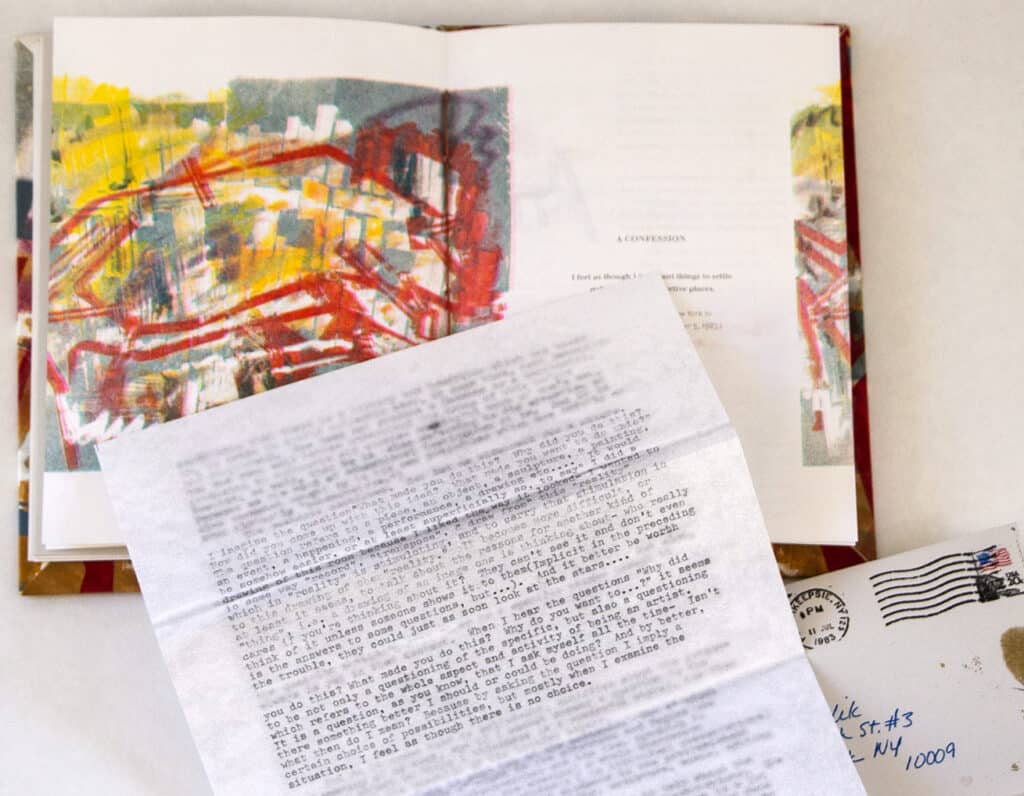

Joan’s letters to me in New York from Europe are on sheets of tissue paper folded into blue airmail envelopes. Her letters to me in Indiana from New York are on regular weight paper in standard business envelopes.

I am loving you across the distance Steven—and because I know you’d somehow understand all this, I’m wishing you were here. (Letter from Joan in New York to Steven in Indiana, November 22, 1983.)

When B. and I and our friend L. with whom we had a band called Two Houses traveled to Europe in 1987 or 88—we called it a tour but it was 3 shows over the course of nearly a month, two in London in a loft squat and a pub, one in a Berlin club—we ended the trip with a week (or two?) in Milan. I caught a cold on the plane from New York and it lingered in raw, wet London, Amsterdam, and Berlin. It must have been spring. We took a train from Germany, through the Alps which we never saw through thick fog, but when we reached Italy the fog lifted, the sun was out and warm, and my cold disappeared.

As for the money thing—I am not “starving” and neither am I wearing rags [. . .]. But, and this is where I qualify why I asked you to send that money you owe—I am trying to plan on the trip to Germany in January—if you can’t send me the money now that’s fine, but I would be needing it when you are coming back here—that was the point. I don’t know how you can work this out except that it might be possible for you to “get a job” or something so mundane as that [. . .]. (Letter from Joan in New York to Steven in Indiana, October 1, 1983.)

Tim was an old friend of my boyfriend B., from Wisconsin, but who lived in Milan then with his Italian lover. Two things I remember about Tim, both stories B. told me: once, before I was around, when Tim stayed with B., B. did his laundry and his white briefs all had wide brown skid marks down the back. Also, maybe on that same visit, Tim had sex with a friend of B.’s who was straight but who nevertheless liked to get fucked now and then. Tim and Pietro were gracious, generous European hosts (Tim was American, but he’d been an expatriate for some time). Pietro cooked us pasta, Tim showed us the park where men cruised and he taught us how to tell the prostitutes from the men who were just looking for quick sex.

Of course I am a Puritan (we are all aware) [. . .]. (Letter from Joan in Hamburg to Steven in New York, December 6, 1984.)

I was surprised to find that the Berlin Wall was not just a wall dividing a city in half, but two long walls on either side of and enclosing the passage from West Germany to the city of Berlin which was completely surrounded by East Germany. We took an overnight train from Amsterdam. We booked sleeper cabins, the kind where six bunks fold out from the walls, three on each side. We were asleep when the train crossed the border entering into the long corridor through East Germany, and immigration officials woke us to examine our passports. It was political theater and I was completely in love with the drama of it on my first trip to Europe, the loud rap on the cabin door in the middle of the night, military uniforms and curt, unintelligible German, the officers’ expressionless glances back and forth between our passports and our bleary faces. Later in our visit, Joan took us to East Berlin to visit a friend, an artist who had been trying, unsuccessfully, for years to get permission to emigrate to the West. She had a poster with an aerial shot or a map, I can’t remember which, of Paris on the wall of her grey, sparsely furnished but homey apartment. She’d never been to Paris, only read about it. I don’t remember what she offered us but I’m sure some kind of refreshment. The matter-of-fact, old-fashioned graciousness of all the Germans we met—if you visited someone’s home, they made you tea or coffee, put out some cookies or fruit—made a lasting impression on me. It wasn’t something we did in New York. Our parents maybe, but not us. We stayed with Joan and her partner at the time, X., and in the morning she’d make us coffee in one of those stovetop espresso pots and cover the whole kitchen table with breads and pastries and pots of preserves and myriad dairy products we’d never seen before. Quark?

You were right about my freaking on your material possessions—I tried to call Eduardo the night you called—no answer—don’t worry though he’s still alive. If you speak with him—drop him a line—tell him to get in touch again here. I really need to get this stuff out of here (no erasure of you, but I feel if I lived on the San Andreas fault things would be flying overhead every minute). (Letter from Joan in New York to Steven in Indiana, August 23, 1983.)

A Confession

I imagine the question “What made you do this? Why did you do this? How did you come up with this idea? What made you want to do this?” The question refers to a piece, an object, a sculpture, a painting, an event, a happening, a performance, a drawing etc. . . It would be somehow easier, or at least superficially so, to say “I did a drawing of this room because I liked the way it looked—I wanted to in some way “record,” “transpose,” “draw from” this “reality” which in “reality” is stimulating, and to carry that stimulation into this drawing of the “reality.” It becomes more difficult, or at least it seems, to talk about the reasons for another kind of “thing,” i.e. a drawing of an image one is thinking about—who really cares if you’re thinking about it? They can’t see it and don’t even think of it unless someone shows it to them (implicit in the preceding is the answers to some questions, but. . .). And it better be worth the trouble, they could just as soon look at the stars. . . [. . .] When I hear the questions “Why did you do this? What made you do this? Why do you want to. . .?” it seems to be not only a questioning of the specific, but also a questioning which refers to the whole aspect and activity of being an artist. It is a question, as you know, that I ask myself all the time—Isn’t there something better I should or could be doing? And by better, what then do I mean? Because by asking the question I imply a certain choice of possibilities, but mostly when I examine the situation, I feel as though there is no choice. (Letter from Joan in Rhinebeck to Steven in New York, July 10, 1983.)

I’ve told this story many times and it never becomes what I wish it were: a parable of non-attachment. Instead, it is always a confession. A confession, saturated with regret, of an unforgivable sin—against art, against a friend, against the line from there to here, then to now.

I’m rambling Steven my dear. I am just missing you—knowing you could tell me in that clear and unfettered way to calm my anxieties—to stop a fretful curiosity—to let myself live my life without continually disrupting faith in myself. (Letter from Joan in New York to Steven in Indiana, November 22, 1983.)

When I left New York in 1998 because J. and I were out of money and had to live somewhere cheaper if we wanted to continue performing and touring—the first of many such leavings of places—we, in order to reduce the size of the truck we would need, separated the objects we owned: keep and not keep. (I remember this time in my life, before I began to mourn things, when purging felt good, felt virtuous, almost religious, I remember that time with a sharp intake of breath and pressure behind my eyes.) Joan had given me many years earlier a painting she made when we were students together. It was large, painted on masonite, of a chair, or many chairs, a pile of furniture, made with drawing-like marks in colorwheel colors like a graph or chart, marks not so much limning the edges of things but the connections between them. I remember her painting it. It was a touchstone painting for her, one of those pieces where you figure something out. It was large and heavy, and I told her I couldn’t take it with me. I knew she was wounded. I left the painting on the street. Not keep.

[. . .] when in reality we know that New York—and occasionally some various parts of foreign country land masses—when and only when they send a stray soul to ports of this City—this City which we all in reality know to be the center, the nexus, the Reality itself. (Letter from Joan in New York to Steven in Indiana, September 2, 1983.)Of course, memory is tricky and I could have this wrong. Maybe it was earlier that I decided I couldn’t keep the painting, an earlier purge. I didn’t own much, could never keep much. Or maybe I took the painting in the truck to Nashville and then later asked Joan to take it back. I’m never certain, except of the stark fact of abandoning the painting.

Blatancy disturbs me. Banality is part and parcel of the literalness attitude of so much of this. I think that there needs to be some other sort of looking that goes beyond the mere recognition of what we think that we are looking at. (Letter from Joan in New York to Steven in Indiana, November 22, 1983.)

Before J. and I drove away, I saw Joan briefly. By 1998, I was living with J. on 10th between First and Second Avenues (the scary block no longer scary). Joan and I had seen less and less of each other through the ’90s—I was preoccupied with my career, she was back and forth to Berlin, and what I remember of that goodbye is that Joan and I were walking across First Avenue from her apartment to mine and in the middle of the Avenue we ran into a friend, a more recent friend and neighbor whom Joan didn’t know, and as this new friend and I talked Joan started to cry, quietly, and I remember being surprised because I thought she was angry and would not be sad to see me go.

Your mattress has been tossed. Bedbug infestation. (What a way to end this.) I love and miss you Steven. (Letter from Joan in New York to Steven in Indiana, November 22, 1983.)