He could barely grip the doorknob as he staggered into the house. Inside, the darkness was thick, heavy, grim. It took a few minutes for his eyes to adjust to the various hues of blackness, for his thumping heart to accommodate the shadings and gradations of fear and dread. The smell of Jack Daniels escaped from his mouth in between hiccups, like puffs of cigarette smoke. He shuffled down the long hallway of the front entrance towards the back of the house where he could hear the hum of the refrigerator. His arm was outstretched and his calloused hand, swollen as though the pulsating flow of blood were threatening to burst the veins, traced the walls. Steady, now. Keep steady. His mind, mired in its own darkness, a devil’s darkness, tried to recall what his friend had laid out as the plan earlier that day . . . .

Go down the hall, check the pantry—behind the canned foods. Money should be there. And if it ain’t, then check the closet.

Where’s the closet?

In the hall. Right there in the hall.

You sure ’bout this?

Damn sure. Money’s there.

The narrow hallway opened up into a larger room—the kitchen. The large window above the sink let in some moonlight. Thank the Lord for the light. He spotted the alcove in the corner of the room, which he took to be the pantry. The cans clinked against each other as he felt behind them for any hint of a stash of money. As he traced the shelf, his fingertips collected some dust which he wiped against his pant leg. Damn! Closet, then. Fool better be right. Money better be there in the closet. The thud of his work boots on the hardwood floor vibrated the darkness as he made his way back to the hallway to check . . . . The fool said it’d be in the closet in the hall. The fool better be right. Damn him if no money is there neither. He found the closet door and he swung it open with little concern for the noise. Grab and go is what he was thinking, what he cared about. He squinted into the black abyss, panting, reaching inside, lurking into the unknown, wondering if this darkness was in fact a closet.

A cold rod pressed against his calf.

“Boom! Like an explosion. I honestly don’t even know how I reacted so quickly, being drunk and all, but I grabbed that shotgun and then I reached into my waistband and grabbed my own gun and just shot into the darkness.” Billy sucked in air, as though it all happened just now.

***

My dad had invited Billy Moore to have dinner with us, the night before he was to give a guest lecture to my dad’s criminal-law class. My dad was a death-penalty lawyer before becoming a law professor. He told me the death penalty had problems in the way it’s administered, throwing out numbers to prove his point, but back then statistics about anything was dull. But stories! That’s a different matter entirely.

Billy reached for his glass of water and took a sip.

“I heard something thump on the floor,” Billy continued, “and when I turned on the light, there he lay.”

Dead? Is he saying the man was dead?

“There was no blood that I could see. He was just lying still.”

Yes, he’s saying he killed the man. There’s a murderer in my house. I’m having dinner with a murderer. A real-life murderer.

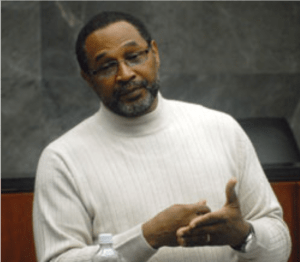

I sat there, as still as this dead man in the story, while my dad and Billy went off on some tangent. I think they were talking about what Billy should say to his class. I hadn’t touched my food yet, hadn’t even moved—I don’t think that’s ever happened to me, finding myself immobilized like that. Billy sat at the head of the table, my mom to his right, my dad to his left, and me next to my dad. He wore a gray turtleneck, dark blue jeans, and loafers. His salt-and-pepper facial hair seemed incongruent with his patchy jet-black Afro. His frameless circular glasses cast a faint shadow on his cheeks as he spoke. I wanted him to return to the story.

He said the State of Georgia wanted to kill him. A date was set and he figured that’s how it would end, how the story of Billy Moore would end. My dad asked about his attorney, something about how the attorney had treated him.

“Oh, well my attorney sent me a letter, three days after my scheduled execution date saying that he forgot to tell me that I wouldn’t be executed that day. My case was going up on appeal. He never explained that to me, what an appeal was, so I was all in the dark.”

This man knows about darkness, I thought to myself. He took another sip of his water and continued. Lots of what he said I couldn’t grasp because my dad wanted to hear about some of the legal nuances he encountered in his fight to overturn his death sentence. Like how ineffective assistance of counsel is ubiquitous when it comes to capital punishment. I kept hearing that phrase, ineffective assistance of counsel, but what did it mean?

Lawyers falling asleep at trial as testimony was being taken: lawyers delivering closing arguments lasting only a few minutes; some even saying that their clients really didn’t deserve any kind of mercy. There are stories of deadly forgetfulness—of lawyers forgetting crucial deadlines, and even of lawyers forgetting that they have clients on death row.

“I was pretty upset,” Billy said. “I mean, being on death row don’t mean you don’t have feelings about whether you’re going to be killed or not on the date they got planned. The man really didn’t care about me or my case. So I told my sister to fire this guy and I filed a petition to the court saying I’d go pro se.”

“What’s pro se, dad?”

“It means representing yourself, sweetheart. It means you’re not going to use a lawyer.”

***

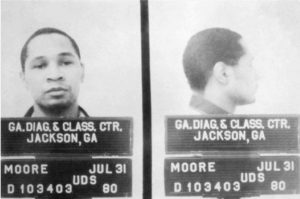

“I was trying to get some money to take care of my son” was William Neal Moore’s rationale for the crime which ultimately landed him on Georgia’s death row. He told me I didn’t need to call him Mr. Moore. “Billy is what people call me.” Sixteen years on death row is bound to take the formality out of a person.

A native of Columbus, Ohio, Billy was, at the time of the break-in and killing, an Army private stationed at Fort Gordon, outside of Augusta, Georgia. One evening he and a few friends were drinking and getting high in the neighboring town of Wrens. One of them disclosed that his uncle lived in the area and kept at least $30,000 hidden in his house. That’s a fortune to an army private living with crushing debt. That’s a fortune to someone who joined the army to escape the violence and gangs of his inner-city community. That’s a fortune to a man who never could take his wife and son out to dinner at a table-cloth restaurant. That’s a fortune, for sure, and it’ll tempt even a God-fearing man. It isn’t an excuse—Billy wanted to make this clear–but it didn’t help things that he was flying higher than a kite, which meant that the regulator in our heads that tells us not to give into temptation—that regulator which keeps a person from doing stupid things–that regulator inside Billy Moore’s head had been deactivated. That’s how the decision to score that fortune slithered its way into his mind.

The first attempt was a bust. “Nothing happened then ’cause the door was locked.”

You might think that good sense would have kicked in, the regulator in his head would have reactivated. You might think that the fear of getting caught would have counteracted the temptation. But that didn’t happen and I was wondering why. I wanted to ask him, Why didn’t you change your mind after that? I didn’t want to be rude, put him on the spot, make him think that some little girl was judging him, so I stayed quiet. I let him continue with his story, of how he did a stupid thing, of how he returned to the house later to try again, and of how he got in that time. Of how he got absorbed into the blackness.

“I pleaded guilty. I did what I did and there was no escaping that. I told the judge I was sorry, really busted up inside about what I’d done. I explained that I didn’t mean to shoot him and for sure didn’t mean to kill him. I explained that I was in a tight spot financially which pushed me to do it.”

“Did your lawyer convince you to plead guilty?” my dad asked.

Billy nodded. He glanced down at his plate. “I was just this young black man and here I’d done killed a white man. There wasn’t much hope for me. My lawyer didn’t let me forget that either.”

Just this young black man

“He told me that’d be the best way to get on the judge’s good side. Told me the judge would show some mercy on me, on account of my taking responsibility and saving the county the money and the trauma of having a jury trial.”

So Billy didn’t get a jury trial, like how it’s shown on television. I used to watch Law and Order, so I knew a bit about trials. Plus, my mom and dad both had experience as criminal defense lawyers, and they weren’t skittish about swapping stories in front of me. I grew up in a milieu of courtroom advocacy. I once got kicked out of a courtroom for crying. I was under a year old, sitting in a stroller, and my dad was trying a case, cross-examining a witness. Supposedly I just let out a burst, shattering the palpable tension. I like to think that my dad was about to drop the hammer on the witness. I remember my mom frequently telling me to keep quiet because daddy’s working and I remember saying goodbye to him over and over because he had to travel to Philadelphia for his work as Mumia Abu Jamal’s defense attorney.1

On July 17, 1974, the judge accepted Billy’s guilty plea for felony-murder and armed-robbery in the first degree. Billy’s lawyer was wrong about the judge being pleased with a guilty plea and thus rewarding Billy with a show of mercy. The judge scheduled his execution for Friday the thirteenth—September 13th, 1974.

I hadn’t known this, but it turns out no one really gets executed on the first scheduled execution date. It always gets postponed because there are legal maneuverings that tangle up the process. I heard Billy say the thirteenth was one of many scheduled execution dates. I heard Billy say that at one point he was seven hours away from his execution. I was eleven, too young to fathom what that must be like.

***

“Hey, Billy, turn on the TV for us. Can’t stand to be here for seventy-two hours just lookin’ at you.”

Billy shook his head. “I don’t want none of that. I want to be in my thoughts.”

One of the guards made a whatever-face and went back to taking notes in his large green notebook which rested on his lap. Standing guard over the last seventy-two hours of a man’s life is grim duty.

The smell of urine burned Billy’s nostrils, something he still hadn’t gotten used to after all of these years. The metal toilet on the right side of the cell, just about sixteen inches from the head of his cot, purred with the occasional jolt when another inmate flushed. The new jumpsuit they had him change into was itchy, especially where he was shaved, down on his calf. Dead-men walking get shaved in certain strategic spots before they’re electrocuted. His Bible and other belongings were put into a box and stashed somewhere. His boots were stripped of their laces.

Suicide isn’t allowed. You can’t cheat the State out of killing you by taking your own life.

“Says here that John Eldon Smith–you know him right?—yeah, well, says here he wailed like a baby for most of his time in this cell.” The officer was reading aloud from the tattered notebook. He kept flipping the pages like he was searching for something specific. His belt partitioned his protruding belly into two, a stark contrast with the other guard, a lanky fellow with limbs which twisted like a vine suffocating a tree.

“Oh, and Ivon Ray Stanley, he didn’t sleep none.” The officer tapped the page with his index finger. “Says here he wanted to be awake before his eternal sleep.”

The officers kept at it, taking turns rattling off what was written in the notebook, macabre notations of how each death-row inmate before Billy had spent their last seventy-two hours before their execution. To know when and how you’re going to die, and to be forced to sit with that knowledge, waiting, waiting–hard to fathom what that’s like. What can be done with knowledge like that? Yell? Punch the air? Curse God?

Billy begged them to stop. These were his friends they were talking about. For ten years they had been in prison together. He didn’t want to remember them this way.

It matters to you what gets into your head when you’re about to die.

“Well, it was either TV or this, and you chose this.” said the pot-bellied officer. The skinny one chuckled.

“Would you rather go on a field trip? Let’s go on a field trip,” continued the chunky officer. He hoisted himself up while emitting an exhaustive grunt. The skinny guard rose as if the wind had pushed him up. It reminded Billy of the birthday streamers he had hung for his son’s third birthday, the year he lost his freedom, which emotionlessly fluttered from the doorframe. Against protocol, they led Billy down the hall to a part of the prison he had never seen before. The door banged behind them as they entered a blinding white room with a long horizontal window on the far wall. Something cloaked in a discolored sheet stood in the center and one of the officers let go of Billy’s arm to approach it.

“Appreciate this,” he said as he pulled the sheet away, like they do on game shows. And voilà, a chair was revealed. It looked like a dentist’s chair–and who’d want to sit in one of those? “When you’re sitting in it you won’t be able to appreciate it. So take a good look now, son.”

***

“And it was at that point that I caved,” Billy said. He rubbed his cheeks and shook his head. My mom told me to eat more of my dinner. Billy smiled at me. I think he knew it was hard to eat a meal and listen to this kind of thing.

“That’s really barbaric,” my mom said.

“It’s so hard to describe, not feeling no more hope.” Billy puckered his lips. “Looking back, I see that I was in a state of shock. When a person goes to jail, you think, ‘Well, at least I still have my life, I still have that.’ But from the state’s perspective, when you are given a sentence of death you are already dead. You begin to see that they consider you a dead person—they just haven’t killed you yet.”

“Death? What y’all know about death?” my dad recited with the southern twang that made him sound like Mick Jagger doing a country tune. He and Billy laughed at his quirky reference to Oliver Stone’s Platoon. It was the scene where Sgt. Barnes, the one with death-knowing eyes and a scar on his cheek, confronted some pot-smoking young soldiers who had not yet discovered the essence of war.

“I had ordered my last meal, so I’d say I know a little something.”

***

“And he does,” my dad said later, referring to the fact that Billy likely knew quite a bit about death. We had congregated around the sink, loading the dishwasher. Billy had left by then. I think he was staying over at the home of another professor.

“How come he didn’t get . . . you know?”

“Executed?”

“I mean, yeah.”

“Well, he represented himself, like he said at dinner. What he didn’t talk about was how he started writing letters to the man’s family, the dead man’s family.”

“He did?”

“Yup. When his legal papers were sent to him, he found the contact info for Mr. Stapleton’s family and began writing them letters.” My dad’s voice was elevated over the noise of the faucet and the clanking of porcelain and metal.

“Okay, and what then?” I asked, stopping for a moment as I waited for him to answer.

“Well, the family forgave him. That’s what got him off death row.” My dad explained that the family spoke out in opposition to his execution and his case was presented at the last minute to the Board of Pardon and Parole.

“I didn’t know if I was going to live or die,” Billy had said. “It wasn’t my choice. It was God’s choice.”

And in the eyes of God, we are all equal.

***

When Billy said that he was just a black man what he was really saying was that there was no point in getting on the witness stand and explaining that the killing was an accident. To be just a black man, Billy was saying, was to understand himself as unworthy of being heard and powerless over his fate.

***

“It’s for you,” the pot-bellied guard said, adjusting his belt.

Billy heard it scratch the ground as it skidded under the metal bars which separated him from his execution. He looked at it for a bit, not out of contemplation or wonder, but at first out of curiosity, and then with melancholy because he figured this would be the last time he would be in contact with the outside world, perhaps the last thing he would ever read. He bent over to pick up the white envelope. He stared at it.

“You gon’ open it?” asked the guard. “Ain’t much time left.”

Billy said nothing. He was entranced by the jarring whiteness of the envelope, this whiteness in this dark place. He stood ramrod stiff, stood tall, stood motionless. He stood there speechless, his mind befogged by the realization that this thing called Life would soon be coming to an end. This envelope was his last glimpse of light before infinite, consuming darkness. Is this what death is–an in-between of everything-ness and nothingness? Of overwhelming emotion and blank callousness? All that Bible reading and still the intuition hits hard that there is nothing awaiting us on the other side because there is no other side. There is only this—the moment we are in. It was enough to make his knees buckle.

“Don’t keep me hanging,” said the guard with a stupid grin. He winked from the wittiness of his pun, “Getting mail on death watch, that’s a new one.”

He sat down on the edge of the bed and held the envelope gently, with care, like how he used to hold his son as an infant and gaze down at his little eyelids which were closed as he slept. His infant son’s eyes had not yet seen evil or hatred. He pretended that this envelope was his baby boy. There was nothing written on the envelope other than his full name which was scratched hastily on the back below the flap. He recognized this handwriting as that of the mother of his son. The paper felt worn as if it had been kept a while before being sent.

Realizing he was moving at a glacial pace, he ripped it open and began to read the letter, its brevity surprising him. It had been feathery-light in his hands but then, as the words sank in, it became leaden, heavy. He began to have trouble sustaining his grip. Not even the greatest strength could hold its unbearable lightness. The envelope and single sheet of paper fluttered to the cement floor.

“My son is not my son,” he whispered as if this was his last breath escaping his mouth. At this moment, in a sudden flash, he felt already dead. He felt he had already let go of It All, as though he had conceded himself to this thing called Death. The dim lighting above seemed to flicker and his consciousness oscillated between hyper-awareness and fragmented delusion.

The time he had spent with his son started to play in his head like a rewinding video cassette; from the moment he touched the belly which carried the child, the child he thought was his, to when he stood in the kitchen of that house, deep in the darkness, thinking of how all that money could be used to make him a better father to this child. He began to question his faith. He began to think that this is what death must be like for a killer, a fool, a family-less criminal like himself. Maybe death for him would be like listlessly floating in an empty vacuum, suffocating on the regrets and shame of his brief and poisoned existence, flashes of the most inconsequential moments juxtaposed with those he wishes he could take back, if only he could take them back, if only he could try again, do what’s right and not be so stupid, so foolish, so deluded by desire. If only he could bring this newfound light into that darkness that had been his life.

The shudder of the toilet awakened him from his dream-like stupor and sound began to faintly pour back into his ears. He rubbed his itchy calf, the smoothness of his hairless skin soothed him as his mind returned to the present. He could hear the hushed exchange between the two guards and the muffled clanging of angry cell doors opening and closing. He focused on the metronomic tempos of the dripping faucet and the ticking clock. Then he rose up and walked over to the bars. The paper rustled in the tight grip of his shaking hand. He looked down at the paper one last time, its wrinkled whiteness again pulling him into a trance. And then his whole world sank into the womb-like darkness.

[1] Perhaps the most politically charged and celebrated death-penalty case since the Rosenbergs in the Fifties, the case of Mumia Abu Jamal highlighted the racial dimensions of capital punishment in America. Mumia was a former Black Panther and noted Philadelphia radio journalist when he was charged with the execution-style murder of a young Philadelphia police officer. His death sentence aroused international protests among activists of all types, as well as high-profile academics, Hollywood celebrities, and left-wing politicians. My father was the chief legal strategist on Mumia’s defense team, which ultimately prevailed in overturning Mumia’s death sentence but left the underlying conviction intact.