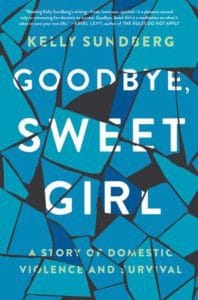

Kelly Sundberg’s essay, “It Will Look Like a Sunset,” originally appeared on Guernica. About domestic abuse, this candid essay went viral, leading her eventually to a book deal: Goodbye, Sweet Girl, to be released June 5th from Harper Collins.

Seems an opportune time to revisit the original essay, so very potent. And also, this essay about her essay, by Melanie Bishop, originally published on Essay Daily.

***

I postponed reading this essay for a few days, even though it had come highly recommended by a friend. A quick glance told me it was about domestic violence, and something made me click on to another essay. Probably the same something that made me postpone seeing Twelve Years a Slave: an aversion to cruelty. Sometimes I let myself be in denial that brutality is as pervasive as it is.

But the title of the essay (pretty), combined with what I’d gleaned the topic to be (not pretty), made me go back looking for it and I’ve now read it half a dozen times. Sundberg succeeds in doing what the best memoirists do–takes disturbing incidents from her life, grapples with them, assigns to them a language and a style, a poetry, thereby elevating the disturbing incidents to the level of art, of beauty. In the process, the difficulty being examined and probed and articulated, goes through a transformation. In preparing the material for a reader, in transforming it to art, Sundberg, I imagine, finds herself having landed on a different shore of her own experience. There’s a view there she’s maybe not seen before, and the air is more fit for breathing. “It Will Look Like a Sunset” is a feat, a gift, a warning, an exorcism, and a cheer. Line by line, it’s an essay that warrants study.

The first paragraph, beautifully spare, is a lesson in economy:

“I was twenty-six, having spent most of my twenties delaying adulthood, and he was twenty-four and enjoyed a reputation as a partier. The pregnancy was a surprise, and we married four months later.”

Each character is introduced with one specific detail, and then bam, surprise pregnancy. Marriage. We’ve slid into the world of this essay with so little fanfare. Another writer might spend pages developing the romance, building the relationship, pondering the pregnancy issue. But Sundberg gets right to the crux matter: two people, a child, a lot of unknowns. A crap shoot. We feel already a foreboding, from only two sentences. The fourth paragraph leaps ahead in time by eight years–Sundberg has skillfully given us the briefest necessary history before dropping readers into the night in question, the night the rest of the essay pivots around. There’s been a bowl dropped on a foot, the resulting break and the bruise and the urgent care doc suggesting the essay’s title. Small paragraphs, separated by space breaks, jumping back and forth in time, replicate a vulnerability and a sense of a disjointed present. “It happened so slowly, then so fast.” A hummingbird in the house foreshadows entrapment, smallness, panic. A scar is described as a star; a bruise as a sunset. Take the ugly and make it pretty.

In a New York Times review of 12 Years a Slave, Manohla Dargis addresses the complexity of the cinematography and the intentional use of conflicting visuals. “There is much to admire about 12 Years a Slave, including the clear-eyed, unsentimental quality of its images — this is a place where trees hang with beautiful moss and black bodies….” Ugliness and beauty, all tangled up together. Sundberg’s rendering of her years in an abusive marriage are equally clear-eyed, unsentimental and tangled. Whether peeing outdoors in the moonlight, seeing baby equipment dismantled by rage, or justifying bruises to concerned friends, Sundberg gives us the truth of these matters, unadorned. She admits to such self-convicting facts as this one: “There are days when I still wish that he would beg me to take him back, promise to change, actually change.” Followed by: “This will never happen.”

Several strategic pairings emerge that bear mention. There’s the pair of cops, one younger and one older, the younger one prone to dismissing domestic violence as normal fighting in a marriage. The older one has seen more in his day, reads more in the busted foot. The errant husband is called back and arrested.

There’s the pairing of phrases that echo in the narrator’s head, which Sundberg puts on repeat for the reader. You are a fucking cunt, countered with It will look like a sunset. She gives us each one eight times, the second series of repetitions meant to cancel out the first, because sunsets are a good thing, right? But even that sunset, the beauty it connotes, is merely an artistic rendering of a violent act, a description of a body broken.

And there’s the pairing of the displaced hummingbird, “trying to turn glass into sky” and, toward the end of the essay, the narrator, small and frantic, crying at her own window, trapped behind her own sky-less glass.

There’s the imagined cave and the actual cave. One, the narrator invents as a place for mental escape during attacks, and the other exists in an old photograph, the narrator’s favorite, from a nice day the couple spent on an Oregon beach. The imaginary cave is deep and dark enough that from there, the physical blows feel distant. The real cave in the photo she remembers had looked inviting, and the narrator had wanted to explore, but feared the rising tide, entrapment and drowning. Every potentially good thing has its perilous twin.

There’s the pairing of the question “Is he going to leave me?” followed by, three lines later, the statement, “He’s going to leave me.” And finally, the paired comments the narrator gets from first the young cop and later, her own mother. Different words but the same sentiment. The young policeman admits that he and his wife fight too, that sometimes things get crazy, suggests getting away, letting things calm down. And the mother warns her daughter that she has seen friends leave their husbands. She warns, “It’s not better on the other side…Try hard before you give up.”

There’s only one “I’m sorry” in the essay, and if it has a twin, we never saw it. The single apology is spoken by the narrator, the victim. (Note: Sundberg’s blog is called Apology Not Accepted.)

When taking notes, I marked one paragraph as a tribute to her ex-husband, Caleb. It starts with the line, “Of everyone I had dated, he was the gentlest.” Another paragraph read like the part of a job application that asks you to list any community service. This was also about her ex, starting with the line, “When our elderly neighbor developed dementia…” and going on to detail numerous sincere and generous acts by Caleb. Finally, another paragraph I marked in the margin with this note: “Reads like an obituary.” This one starts with “We were one of those couples that others liked to be around,” and goes on to carefully paint this relationship—its humor, mutual respect, shared meals, TV shows, and travels. All of these sections mentioned are noteworthy for their economy, precision, and consistency of style, but the one that reads like an obit hits the most potent emotional chord. When looking back at the photo of the best day together, on the Oregon beach, the smiling man and woman with their heads pressed together, the narrator says, “Where are those people? Where did they go?” Those two people died. They are no more, and the obituary paragraph is fitting.

I couldn’t avoid seeing 12 Years a Slave any longer. The Academy Awards were about to air, and I needed to see all the big contenders. Throughout the film, I had to hide my eyes. My husband would tell me when it was safe to start watching again. There were many times when I couldn’t watch, but the worst was when Solomon is forced to deliver the lashings to his friend and ally, Patsey. Truthfully, it was the only part of the film I didn’t believe. I don’t question that he might be forced to deliver the blows, that this would offer up some variety, provide some other layer of fascination or entertainment for the evil slave owners, but I thought Solomon, as we’d come to know his character, would’ve put up more of a fight before succumbing. I heard myself involuntarily vocalizing in the crowded theater. (Embarrassing.) “NO!” I said. “He would refuse to do that!” But then he was doing it and I buried my head till it was safe to come up again. The equivalent part in Sundberg’s essay, the part where I would hide my eyes, the part I’ll not be able to shed, is the moment of fist to spine. Bruises are one thing. Yanked hair. Even a busted foot. But when her abuser went for her backbone, he was aiming to do structural damage, to give her skeleton a memory, a point on a timeline it would never forget.

Given all this essay accomplishes, what I most admire, finally, is Sundberg’s ability to persuade. We come out of her essay believing that a partner can be both loving and dangerous. Warm and monstrous. A good father and a frightening husband. I admire the care she takes to present a fair and three-dimensional portrait of her abuser. She tells us he was more often kind than unkind. She says, simply, “We respected each other.” Even on the worst nights, when she seeks refuge at a local Travelodge, she returns home before morning, “…climbing into bed and wrapping my arms around Caleb’s back.” She admits, “I still loved him. I told myself he would get better.” Heartbreaking. Complicated. True. I have not stopped thinking about this essay, and plan to read—next time without delay—anything Kelly Sundberg writes. Bravo.